Last December, I returned to Qursaya, a small island on the Nile in the middle of Cairo, with a notebook full of ideas. One of my main goals was to prepare for the Nile Parade on the occasion of Nile Day, usually celebrated every 22nd of February by the eleven Nile Basin countries.

I started the Nile Parade last year as part of my Master’s research on myths, rituals, and their connection to environmental sustainability. Inspired by ancient Egyptian traditions, the first Nile Parade was fully voluntary, made possible by the enthusiasm and dedication of those who joined me—artists, fishermen, children, women of Qursaya, and the team of Very Nile, an environmental organisation based on the island and focused on cleaning the river and raising awareness about plastic pollution. Though it was a small community celebration rather than a public event, the first Nile Parade resulted in a powerful reaffirmation of the deep connection between people and the river.

Why Qursaya?

For years, I have been working on stories about the Nile, but I came to realize that no single project could capture its full complexity. The story of the Nile never ends. It meanders, branches, and loops back, always revealing something new. Instead of attempting to tell the whole story at once, I decided to zoom in, focusing on a single place that could serve as a microcosm of the Nile itself.

Qursaya Island is that place. Located in the heart of Cairo — a city of over 22 million people — it remains a world apart: a community of fishermen and farmers, accessible only by ferry or the small boats of the fishermen. The VeryNile project, which collaborates with fishermen to collect plastic waste from the Nile for recycling, adds another layer to its significance. So does the Pharaonic Village, a tourist attraction that mimics life in ancient Egypt. That’s why, for me, Qursaya feels like a microcosm of the Nile—a place where past and present coexist, where environmental degradation meets grassroots action, and where a community shaped by the river now grapples with its deteriorating ecosystem. Here, you can witness the full spectrum of the Nile's realities: cultural memory, ecological damage, economic struggle, and local resilience, all surrounded by water, yet still confronting water scarcity.

This time, I arrived with a long to-do list, eager for new knowledge and discoveries. Alongside planning for the Nile Parade, I also wanted to deepen my research on the water and the Nile around Qursaya, this time in direct collaboration with the fishermen themselves.

The Fishermen’s Workshop: A Conversation on the Nile

As a part of this research, I organized a workshop for the fishermen to create a genuine collaborative exchange instead of merely using their experiences to implement my vision. Collaboration is a delicate balance, and I wanted to ensure that this was a space for shared knowledge, not just a one-way process.

To facilitate this, I partnered with urban sociologist Saker El Nour, and together we organized two workshops that brought together 31 fishermen from Qursaya and a neighboring island. The initial goal was to give voice to the fishermen, centering their lived experiences on and around the Nile. We aimed to engage them in the preparation and participation in the Nile Parade by listening to their stories, understanding the challenges they face, and hearing their ideas for solutions. We didn’t know what to expect, but the conversations that unfolded were more insightful than we had imagined. It became a special and meaningful moment: for the first time, many of the fishermen — who normally only cross paths briefly on the island or in their boats — gathered in one space. It was a space not only for sharing but also for disagreement, debate, and dialogue, a forum that allowed for collective reflection and, perhaps, the beginning of a shared voice.

One of the most striking moments was when Saker opened the discussion with a simple question:

"What is your most memorable moment on the Nile?"

Mohamed, one of the fishermen, was the first to answer.

"I once caught a fish that weighed 15 kilos. That was many years ago."

From there, the room came alive. One by one, the fishermen started recalling their biggest catches: 6 kilos, 10 kilos, even 17 kilos! But these stories were all from the past. Today, every single fisherman in the room works with VeryNile, collecting plastic waste rather than relying on fishing alone, because the fish stock in the Nile has declined drastically.

Another eye-opening moment came when Saker distributed printed images of different fish species and asked the fishermen to identify which ones still existed in the Nile. This simple exercise sparked intense discussions about names, species, and whether certain fish had disappeared entirely. It was a powerful way to reactivate our memories and make us reflect on how the Nile has changed over time.

After the workshop, Saker and I sat in a café, sipping tea and reflecting. We were both struck by how engaged the fishermen had been. Their knowledge was profound, and they saw details about the Nile that often go unnoticed. This experience made us even more eager to expand the project, to let the fishermen guide us through their Nile, sharing their knowledge about fish, water, and life on the river. One idea that emerged was to create a "Manual of Life Around Qursaya", documenting their observations on species, microorganisms, water quality, and the daily challenges they face.

A Water Tour with Arafa: Learning from the River and the Fisherman

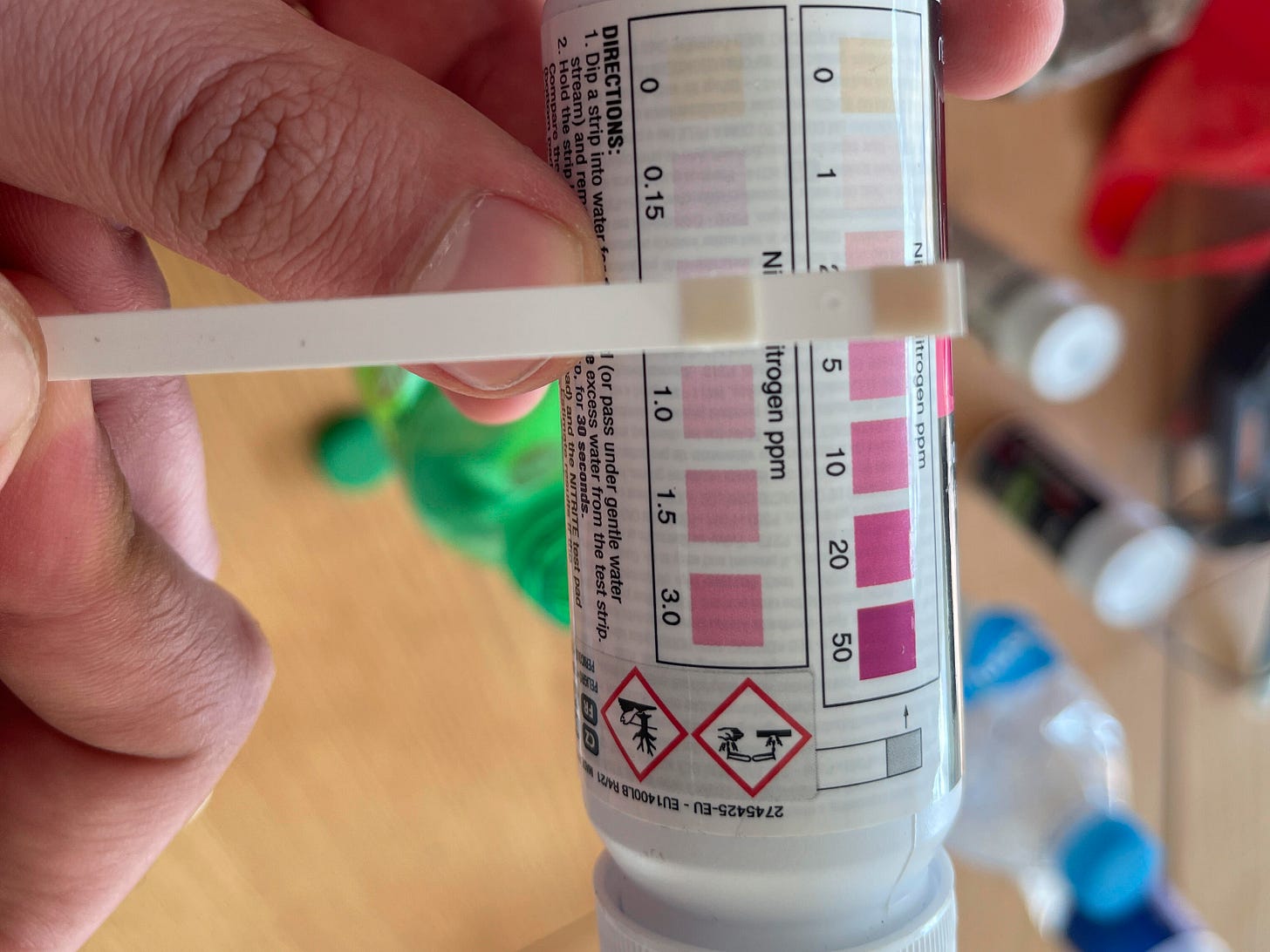

Parallel to this, I had also invited Omar Magdi, a PhD researcher from Delft, to join me in exploring the water quality around Qursaya. We planned a preliminary sampling campaign to collect water samples from several locations around the island. Borrowing simple water testing tools from the IHE Delft lab, we set out on a journey with Arafa, a leading fisherman and friend from the island, to collect the samples and better understand the condition of the river.

For three hours, we navigated the Nile in Arafa’s small boat, stopping at different points to collect water samples. The results were striking. Some areas were highly polluted. Others had unusual colors. Some samples contained silt from the riverbed. Others, taken from the middle of the river, appeared relatively cleaner.

But beyond gathering samples, this trip became an unexpected masterclass in river ecology. As we floated along, Arafa shared story after story, pointing out invasive species, explaining fishing techniques, and identifying which native species had disappeared. His knowledge, gained from a lifetime on the water, was as valuable as any scientific study.

Back at VeryNile, we worked on interpreting the samples and the captured photographs in relation to water quality. We conducted both analytical and microscopic tests.

Our findings indicated potential pollution at certain sampling points, likely due to a combination of inadequate sanitation services on the island, direct disposal of household waste into the Nile, littering along the banks, and the lack of effective waste management infrastructure. While this serves as an important indicator, further research with a structured seasonal campaign is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the situation.

What’s Next? Preparing for the Nile Parade

At this stage, I decided to pause my water experiments and focus on the upcoming Nile Parade celebration. This year, we planned to expand it further, introducing a performance by the fishermen, a "Kids of the Nile" show, and an #EverydayNile photo exhibition.

With a team of over 20 people, we all worked hard trying to make it happen.

Beyond that, my longer-term research on Qursaya is only beginning. I want to continue working with the fishermen, scientists, and artists—bridging traditional knowledge with contemporary environmental research.

Every time I think I have reached a conclusion, the Nile proves me wrong. It is an endless stream of connections, ideas, and discoveries. To be continued...

Roger Anis is an artist-in-residence at IHE Delft within the Aquamuse project.

Originally posted on Flows: The Water Governance Blog at IHE Delft Institute of Water Education by Roger Anis